While watching an old interview of Muhammad Ali which popped up on my phone screen it occurred to me that I have never sat across a table and had a real conversation with a black man or woman. I consider this one of the gaps in my experience despite my travels and my interest in conversations with people whose culture and lived experiences are different from mine. Yet through books and films, I grew familiar with black lives when I was quite young. Beginning with Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Over the years I read about the slave ships that crossed the Atlantic, the plantations where lives were broken, and also the fierce dignity that rose from oppression. I have read James Baldwin and Richard Wright, read and watched Roots, and admired actors like Sidney Poitier who brought depth and grace to the screen. And in my boyhood, Muhammad Ali loomed larger than life – an athlete, rebel, and poet rolled into one.

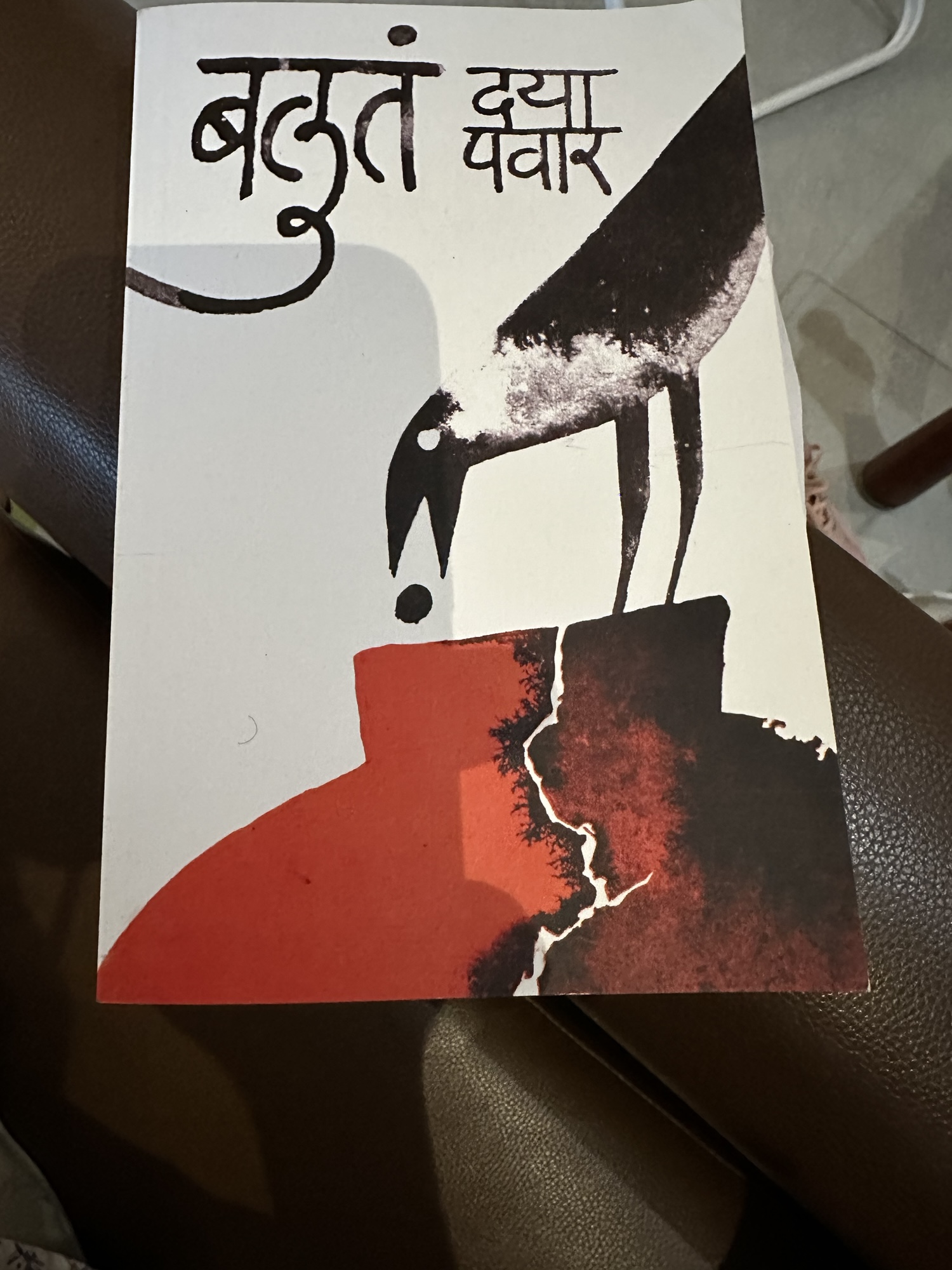

In the next moment, with a recently acquired copy of Marathi Dalit writer Daya Pawar’s book Baluta lying in front of me, it occurred to me that as a young person I had a more intimate sense of the struggles of black people in America than of Dalits in my own country. ‘ Dalits’, a word I learned much later, were identified in conversations by their earlier caste names and the kind of work they did. I learnt through education to refer to them as Harijans. Educated Indian minds could rest assured that equality before the law and positive discrimination by implementing education and job reservation quotas were the solution to historical exclusion. Because our constitution had ensured that. Instead of guilt about the past there was pride about our collective kindness towards the ‘Harijans’ in accordance with ‘ modern’ ideas of democracy and equality before the law.

The history text books we read were “balanced” and bland – lists of reformers and leaders, social evils “eradicated,” milestones achieved. There were references to Gandhi, Nehru, Patel, Subhash – names every child knew by heart. Ambedkar’s name was there too, but more as a framer of the Constitution than as a thinker, writer, or revolutionary whose words might unsettle. Untouchability was acknowledged as an undesirable social practice, one that our enlightened reformers had worked hard to ‘abolish’. In some discussions I have heard over the years – and I still hear- the ‘caste system’ of the past is explained as a brilliant division of labour which worked perfectly for the economy of the past but is no longer necessary. Hence the progressive ‘reforms’ – through legislation

Despite my natural sympathy for the poor as a boy and my anger at any instance of any poor ‘servant boy’ being scolded by any relative for some mistake or misdemeanour in a manner that seemed excessive or unfair, the lived reality of Dalit lives was not something that was apparent to me. Although there were ‘ servant boys’ from poor rural families working as domestic help in homes but they were not Dalits. I was barely aware of the existence of the individuals who cleared ‘ night soil’ from traditional toilets – without having to enter homes.

I heard no stories about Dalit lives although I heard all kinds of stories from all kinds of people. Which included stories from teenager servant boys about life in their villages. Any reference to any Dalit – by their original caste names – was incidental to any story. No Dalit was a protagonist in any story I heard as child. Not even as a minor character. Dalits were outside the pale of non-Dalit consciousness as it were. Or on the periphery. Silent – and almost invisible. Without the drama of the visible lives of slaves owned by people or serfs serving their feudal lords. Where there was scope for cruelty or compassion, conflict or sacrifice. And therefore stories. In contrast the Dalits were simply creatures who did the dirty work of scavengers for the community and were expected to keep a safe and silent distance from every asset and amenity of the community – wells, temples or schools and ‘public spaces’. According to the rules of social and personal hygiene – as ordained by tradition. Rules which did not apply to domestic animals who lived in close proximity – and therefore featured sometimes in stories I heard. Cows were worshipped. Dogs were pets. Cats were fed.

Discrimination and exploitation are not always visible or even deliberate. They can be structural. And made acceptable by a world view which suggests that every body’s status at birth is the result of the Karma of their previous life. And that the Varnashram system was the perfect framework for organising the economy and society in the past in the Indian sub-continent.

In my school and college years, I did not even know that Dalit literature existed as a genre. A few ‘art’ films of the 1970s and 1980s – Govind Nihalani’s Aakrosh and Ardh Satya, Shyam Benegal’s Ankur – touched on caste, but Bollywood cinema mostly dramatised the feudal exploitation of farmers by zamindars or the capitalist exploitation of workers. Dalits, if they appeared at all, were barely visible figures in the background.

It was only when I began my career as a civil servant in Maharashtra that the gaps in my understanding became too stark to ignore. They could be filled only through my own quest to understand the social fabric and the reality of Dalit lives – beyond the symbolism and rhetoric of politics . Reading Ambedkar properly for the first time was like discovering a new grammar of Indian history. Annihilation of Caste was searing. The writings of scholars like M. N. Srinivas or Rajni Kothari, valuable though they were in explaining the sociology and politics of caste, had not told me what it felt like to be Dalit.

That truth came through literature – English translations, to begin with. Omprakash Valmiki’s Joothan, with its painful memories of humiliation; Daya Pawar’s Baluta, the first Dalit autobiography that broke the silence of Marathi literature; Baburao Bagul’s stark and uncompromising stories in When I Hid My Caste; and the poetry of Namdeo Dhasal that burned with anger and dark music. These works opened windows I had not known existed. They were not sociological analyses but living testimonies – voices that spoke of indignity and exclusion, but also of resilience, creativity, and the fierce hunger for equality.

Looking back, I sometimes wonder: how did I, who had read Baldwin and Angelou, remain blind to Valmiki and Pawar until much later? Perhaps it is because of the silence we inherit, the selective amnesia of our textbooks and media, the comfortable ideals and sanitised narratives of progress. Literature, when it is true, does not let you look away. It forces you to imagine lives other than your own.

———